Branch of medicine

- Sub-Millimeter Surgical Dexterity

- Knowledge of human health, disease, pathology, and anatomy

- Communication/Interpersonal Skills

- Analytical Skills

- Critical Thinking

- Empathy/Professionalism

- Private practices

- Primary care clinics

- Hospitals

- Physician

- dental assistant

- dental technician

- dental hygienist

- various dental specialists

Dentistry

A dentist treats a patient with the help of a dental assistant.

|

| Names |

- Dentist

- Dental Surgeon

- Doctor

[1][nb 1]

|

|

Occupation type

|

Profession |

|

Activity sectors

|

Health care, Anatomy, Physiology, Pathology, Medicine, Pharmacology, Surgery |

| Competencies |

|

|

Education required

|

Dental Degree |

|

Fields of

employment

|

|

|

Related jobs

|

|

Medical intervention

| ICD-9-CM |

23-24 |

| MeSH |

D003813 |

|

[edit on Wikidata]

|

An oral surgeon and dental assistant removing a wisdom tooth

An oral surgeon and dental assistant removing a wisdom tooth

Dentistry, also known as dental medicine and oral medicine, is the branch of medicine focused on the teeth, gums, and mouth. It consists of the study, diagnosis, prevention, management, and treatment of diseases, disorders, and conditions of the mouth, most commonly focused on dentition (the development and arrangement of teeth) as well as the oral mucosa.[2] Dentistry may also encompass other aspects of the craniofacial complex including the temporomandibular joint. The practitioner is called a dentist.

The history of dentistry is almost as ancient as the history of humanity and civilization, with the earliest evidence dating from 7000 BC to 5500 BC.[3] Dentistry is thought to have been the first specialization in medicine which has gone on to develop its own accredited degree with its own specializations.[4] Dentistry is often also understood to subsume the now largely defunct medical specialty of stomatology (the study of the mouth and its disorders and diseases) for which reason the two terms are used interchangeably in certain regions. However, some specialties such as oral and maxillofacial surgery (facial reconstruction) may require both medical and dental degrees to accomplish. In European history, dentistry is considered to have stemmed from the trade of barber surgeons.[5]

Dental treatments are carried out by a dental team, which often consists of a dentist and dental auxiliaries (such as dental assistants, dental hygienists, dental technicians, and dental therapists). Most dentists either work in private practices (primary care), dental hospitals, or (secondary care) institutions (prisons, armed forces bases, etc.).

The modern movement of evidence-based dentistry calls for the use of high-quality scientific research and evidence to guide decision-making such as in manual tooth conservation, use of fluoride water treatment and fluoride toothpaste, dealing with oral diseases such as tooth decay and periodontitis, as well as systematic diseases such as osteoporosis, diabetes, celiac disease, cancer, and HIV/AIDS which could also affect the oral cavity. Other practices relevant to evidence-based dentistry include radiology of the mouth to inspect teeth deformity or oral malaises, haematology (study of blood) to avoid bleeding complications during dental surgery, cardiology (due to various severe complications arising from dental surgery with patients with heart disease), etc.

Terminology

[edit]

The term dentistry comes from dentist, which comes from French dentiste, which comes from the French and Latin words for tooth.[6] The term for the associated scientific study of teeth is odontology (from Ancient Greek: á½€δοÃÂÂÂς, romanized: odoús, lit. 'tooth') – the study of the structure, development, and abnormalities of the teeth.

Dental treatment

[edit]

Dentistry usually encompasses practices related to the oral cavity.[7] According to the World Health Organization, oral diseases are major public health problems due to their high incidence and prevalence across the globe, with the disadvantaged affected more than other socio-economic groups.[8]

The majority of dental treatments are carried out to prevent or treat the two most common oral diseases which are dental caries (tooth decay) and periodontal disease (gum disease or pyorrhea). Common treatments involve the restoration of teeth, extraction or surgical removal of teeth, scaling and root planing, endodontic root canal treatment, and cosmetic dentistry[9]

By nature of their general training, dentists, without specialization can carry out the majority of dental treatments such as restorative (fillings, crowns, bridges), prosthetic (dentures), endodontic (root canal) therapy, periodontal (gum) therapy, and extraction of teeth, as well as performing examinations, radiographs (x-rays), and diagnosis. Dentists can also prescribe medications used in the field such as antibiotics, sedatives, and any other drugs used in patient management. Depending on their licensing boards, general dentists may be required to complete additional training to perform sedation, dental implants, etc.

Irreversible enamel defects caused by an untreated celiac disease. They may be the only clue to its diagnosis, even in absence of gastrointestinal symptoms, but are often confused with fluorosis, tetracycline discoloration, acid reflux or other causes.[10][11][12] The National Institutes of Health include a dental exam in the diagnostic protocol of celiac disease.[10]

Irreversible enamel defects caused by an untreated celiac disease. They may be the only clue to its diagnosis, even in absence of gastrointestinal symptoms, but are often confused with fluorosis, tetracycline discoloration, acid reflux or other causes.[10][11][12] The National Institutes of Health include a dental exam in the diagnostic protocol of celiac disease.[10]

Dentists also encourage the prevention of oral diseases through proper hygiene and regular, twice or more yearly, checkups for professional cleaning and evaluation. Oral infections and inflammations may affect overall health and conditions in the oral cavity may be indicative of systemic diseases, such as osteoporosis, diabetes, celiac disease or cancer.[7][10][13][14] Many studies have also shown that gum disease is associated with an increased risk of diabetes, heart disease, and preterm birth. The concept that oral health can affect systemic health and disease is referred to as "oral-systemic health".

Education and licensing

[edit]

Main article: Dentistry throughout the world

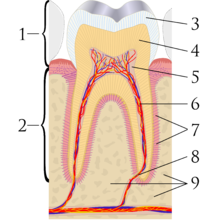

A sagittal cross-section of a molar tooth; 1: crown, 2: root, 3: enamel, 4: dentin and dentin tubules, 5: pulp chamber, 6: blood vessels and nerve, 7: periodontal ligament, 8: apex and periapical region, 9: alveolar bone

A sagittal cross-section of a molar tooth; 1: crown, 2: root, 3: enamel, 4: dentin and dentin tubules, 5: pulp chamber, 6: blood vessels and nerve, 7: periodontal ligament, 8: apex and periapical region, 9: alveolar bone

Early dental chair in Pioneer West Museum in Shamrock, Texas

Early dental chair in Pioneer West Museum in Shamrock, Texas

John M. Harris started the world's first dental school in Bainbridge, Ohio, and helped to establish dentistry as a health profession. It opened on 21 February 1828, and today is a dental museum.[15] The first dental college, Baltimore College of Dental Surgery, opened in Baltimore, Maryland, US in 1840. The second in the United States was the Ohio College of Dental Surgery, established in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1845.[16] The Philadelphia College of Dental Surgery followed in 1852.[17] In 1907, Temple University accepted a bid to incorporate the school.

Studies show that dentists that graduated from different countries,[18] or even from different dental schools in one country,[19] may make different clinical decisions for the same clinical condition. For example, dentists that graduated from Israeli dental schools may recommend the removal of asymptomatic impacted third molar (wisdom teeth) more often than dentists that graduated from Latin American or Eastern European dental schools.[20]

In the United Kingdom, the first dental schools, the London School of Dental Surgery and the Metropolitan School of Dental Science, both in London, opened in 1859.[21] The British Dentists Act of 1878 and the 1879 Dentists Register limited the title of "dentist" and "dental surgeon" to qualified and registered practitioners.[22][23] However, others could legally describe themselves as "dental experts" or "dental consultants".[24] The practice of dentistry in the United Kingdom became fully regulated with the 1921 Dentists Act, which required the registration of anyone practising dentistry.[25] The British Dental Association, formed in 1880 with Sir John Tomes as president, played a major role in prosecuting dentists practising illegally.[22] Dentists in the United Kingdom are now regulated by the General Dental Council.

In many countries, dentists usually complete between five and eight years of post-secondary education before practising. Though not mandatory, many dentists choose to complete an internship or residency focusing on specific aspects of dental care after they have received their dental degree. In a few countries, to become a qualified dentist one must usually complete at least four years of postgraduate study;[26] Dental degrees awarded around the world include the Doctor of Dental Surgery (DDS) and Doctor of Dental Medicine (DMD) in North America (US and Canada), and the Bachelor of Dental Surgery/Baccalaureus Dentalis Chirurgiae (BDS, BDent, BChD, BDSc) in the UK and current and former British Commonwealth countries.

All dentists in the United States undergo at least three years of undergraduate studies, but nearly all complete a bachelor's degree. This schooling is followed by four years of dental school to qualify as a "Doctor of Dental Surgery" (DDS) or "Doctor of Dental Medicine" (DMD). Specialization in dentistry is available in the fields of Anesthesiology, Dental Public Health, Endodontics, Oral Radiology, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Oral Medicine, Orofacial Pain, Pathology, Orthodontics, Pediatric Dentistry (Pedodontics), Periodontics, and Prosthodontics.[27]

Specialties

[edit]

Main article: Specialty (dentistry)

A modern dental clinic in Lappeenranta, Finland

A modern dental clinic in Lappeenranta, Finland

Some dentists undertake further training after their initial degree in order to specialize. Exactly which subjects are recognized by dental registration bodies varies according to location. Examples include:

- Anesthesiology[28] – The specialty of dentistry that deals with the advanced use of general anesthesia, sedation and pain management to facilitate dental procedures.

- Cosmetic dentistry – Focuses on improving the appearance of the mouth, teeth and smile.

- Dental public health – The study of epidemiology and social health policies relevant to oral health.

- Endodontics (also called endodontology) – Root canal therapy and study of diseases of the dental pulp and periapical tissues.

- Forensic odontology – The gathering and use of dental evidence in law. This may be performed by any dentist with experience or training in this field. The function of the forensic dentist is primarily documentation and verification of identity.

- Geriatric dentistry or geriodontics – The delivery of dental care to older adults involving the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of problems associated with normal aging and age-related diseases as part of an interdisciplinary team with other health care professionals.

- Oral and maxillofacial pathology – The study, diagnosis, and sometimes the treatment of oral and maxillofacial related diseases.

- Oral and maxillofacial radiology – The study and radiologic interpretation of oral and maxillofacial diseases.

- Oral and maxillofacial surgery (also called oral surgery) – Extractions, implants, and surgery of the jaws, mouth and face.[nb 2]

- Oral biology – Research in dental and craniofacial biology

- Oral Implantology – The art and science of replacing extracted teeth with dental implants.

- Oral medicine – The clinical evaluation and diagnosis of oral mucosal diseases

- Orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics – The straightening of teeth and modification of midface and mandibular growth.

- Pediatric dentistry (also called pedodontics) – Dentistry for children

- Periodontology (also called periodontics) – The study and treatment of diseases of the periodontium (non-surgical and surgical) as well as placement and maintenance of dental implants

- Prosthodontics (also called prosthetic dentistry) – Dentures, bridges and the restoration of implants.

- Some prosthodontists super-specialize in maxillofacial prosthetics, which is the discipline originally concerned with the rehabilitation of patients with congenital facial and oral defects such as cleft lip and palate or patients born with an underdeveloped ear (microtia). Today, most maxillofacial prosthodontists return function and esthetics to patients with acquired defects secondary to surgical removal of head and neck tumors, or secondary to trauma from war or motor vehicle accidents.

- Special needs dentistry (also called special care dentistry) – Dentistry for those with developmental and acquired disabilities.

- Sports dentistry – the branch of sports medicine dealing with prevention and treatment of dental injuries and oral diseases associated with sports and exercise.[29] The sports dentist works as an individual consultant or as a member of the Sports Medicine Team.

- Veterinary dentistry – The field of dentistry applied to the care of animals. It is a specialty of veterinary medicine.[30][31]

History

[edit]

See also: History of dental treatments

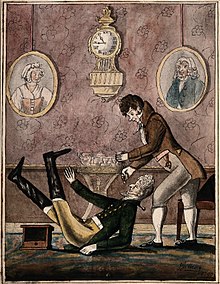

A wealthy patient falling over because of having a tooth extracted with such vigour by a fashionable dentist, c. 1790. History of Dentistry.

A wealthy patient falling over because of having a tooth extracted with such vigour by a fashionable dentist, c. 1790. History of Dentistry.

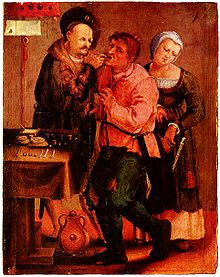

Farmer at the dentist, Johann Liss, c. 1616–17

Farmer at the dentist, Johann Liss, c. 1616–17

Tooth decay was low in pre-agricultural societies, but the advent of farming society about 10,000 years ago correlated with an increase in tooth decay (cavities).[32] An infected tooth from Italy partially cleaned with flint tools, between 13,820 and 14,160 years old, represents the oldest known dentistry,[33] although a 2017 study suggests that 130,000 years ago the Neanderthals already used rudimentary dentistry tools.[34] In Italy evidence dated to the Paleolithic, around 13,000 years ago, points to bitumen used to fill a tooth[35] and in Neolithic Slovenia, 6500 years ago, beeswax was used to close a fracture in a tooth.[36] The Indus valley has yielded evidence of dentistry being practised as far back as 7000 BC, during the Stone Age.[37] The Neolithic site of Mehrgarh (now in Pakistan's south western province of Balochistan) indicates that this form of dentistry involved curing tooth related disorders with bow drills operated, perhaps, by skilled bead-crafters.[3] The reconstruction of this ancient form of dentistry showed that the methods used were reliable and effective.[38] The earliest dental filling, made of beeswax, was discovered in Slovenia and dates from 6500 years ago.[39] Dentistry was practised in prehistoric Malta, as evidenced by a skull which had a dental abscess lanced from the root of a tooth dating back to around 2500 BC.[40]

An ancient Sumerian text describes a "tooth worm" as the cause of dental caries.[41] Evidence of this belief has also been found in ancient India, Egypt, Japan, and China. The legend of the worm is also found in the Homeric Hymns,[42] and as late as the 14th century AD the surgeon Guy de Chauliac still promoted the belief that worms cause tooth decay.[43]

Recipes for the treatment of toothache, infections and loose teeth are spread throughout the Ebers Papyrus, Kahun Papyri, Brugsch Papyrus, and Hearst papyrus of Ancient Egypt.[44] The Edwin Smith Papyrus, written in the 17th century BC but which may reflect previous manuscripts from as early as 3000 BC, discusses the treatment of dislocated or fractured jaws.[44][45] In the 18th century BC, the Code of Hammurabi referenced dental extraction twice as it related to punishment.[46] Examination of the remains of some ancient Egyptians and Greco-Romans reveals early attempts at dental prosthetics.[47] However, it is possible the prosthetics were prepared after death for aesthetic reasons.[44]

Ancient Greek scholars Hippocrates and Aristotle wrote about dentistry, including the eruption pattern of teeth, treating decayed teeth and gum disease, extracting teeth with forceps, and using wires to stabilize loose teeth and fractured jaws.[48] Use of dental appliances, bridges and dentures was applied by the Etruscans in northern Italy, from as early as 700 BC, of human or other animal teeth fastened together with gold bands.[49][50][51] The Romans had likely borrowed this technique by the 5th century BC.[50][52] The Phoenicians crafted dentures during the 6th–4th century BC, fashioning them from gold wire and incorporating two ivory teeth.[53] In ancient Egypt, Hesy-Ra is the first named "dentist" (greatest of the teeth). The Egyptians bound replacement teeth together with gold wire. Roman medical writer Cornelius Celsus wrote extensively of oral diseases as well as dental treatments such as narcotic-containing emollients and astringents.[54] The earliest dental amalgams were first documented in a Tang dynasty medical text written by the Chinese physician Su Kung in 659, and appeared in Germany in 1528.[55][56]

During the Islamic Golden Age Dentistry was discussed in several famous books of medicine such as The Canon in medicine written by Avicenna and Al-Tasreef by Al-Zahrawi who is considered the greatest surgeon of the Middle Ages,[57] Avicenna said that jaw fracture should be reduced according to the occlusal guidance of the teeth; this principle is still valid in modern times. Al-Zahrawi invented over 200 surgical tools that resemble the modern kind.[58]

Historically, dental extractions have been used to treat a variety of illnesses. During the Middle Ages and throughout the 19th century, dentistry was not a profession in itself, and often dental procedures were performed by barbers or general physicians. Barbers usually limited their practice to extracting teeth which alleviated pain and associated chronic tooth infection. Instruments used for dental extractions date back several centuries. In the 14th century, Guy de Chauliac most probably invented the dental pelican[59] (resembling a pelican's beak) which was used to perform dental extractions up until the late 18th century. The pelican was replaced by the dental key[60] which, in turn, was replaced by modern forceps in the 19th century.[61]

Dental needle-nose pliers designed by Fauchard in the late 17th century to use in prosthodontics

Dental needle-nose pliers designed by Fauchard in the late 17th century to use in prosthodontics

The first book focused solely on dentistry was the "Artzney Buchlein" in 1530,[48] and the first dental textbook written in English was called "Operator for the Teeth" by Charles Allen in 1685.[23]

In the United Kingdom, there was no formal qualification for the providers of dental treatment until 1859 and it was only in 1921 that the practice of dentistry was limited to those who were professionally qualified. The Royal Commission on the National Health Service in 1979 reported that there were then more than twice as many registered dentists per 10,000 population in the UK than there were in 1921.[62]

Modern dentistry

[edit]

A microscopic device used in dental analysis, c. 1907

A microscopic device used in dental analysis, c. 1907

It was between 1650 and 1800 that the science of modern dentistry developed. The English physician Thomas Browne in his A Letter to a Friend (c. 1656 pub. 1690) made an early dental observation with characteristic humour:

The Egyptian Mummies that I have seen, have had their Mouths open, and somewhat gaping, which affordeth a good opportunity to view and observe their Teeth, wherein 'tis not easie to find any wanting or decayed: and therefore in Egypt, where one Man practised but one Operation, or the Diseases but of single Parts, it must needs be a barren Profession to confine unto that of drawing of Teeth, and little better than to have been Tooth-drawer unto King Pyrrhus, who had but two in his Head.

The French surgeon Pierre Fauchard became known as the "father of modern dentistry". Despite the limitations of the primitive surgical instruments during the late 17th and early 18th century, Fauchard was a highly skilled surgeon who made remarkable improvisations of dental instruments, often adapting tools from watchmakers, jewelers and even barbers, that he thought could be used in dentistry. He introduced dental fillings as treatment for dental cavities. He asserted that sugar-derived acids like tartaric acid were responsible for dental decay, and also suggested that tumors surrounding the teeth and in the gums could appear in the later stages of tooth decay.[63][64]

Panoramic radiograph of historic dental implants, made 1978

Panoramic radiograph of historic dental implants, made 1978

Fauchard was the pioneer of dental prosthesis, and he invented many methods to replace lost teeth. He suggested that substitutes could be made from carved blocks of ivory or bone. He also introduced dental braces, although they were initially made of gold, he discovered that the teeth position could be corrected as the teeth would follow the pattern of the wires. Waxed linen or silk threads were usually employed to fasten the braces. His contributions to the world of dental science consist primarily of his 1728 publication Le chirurgien dentiste or The Surgeon Dentist. The French text included "basic oral anatomy and function, dental construction, and various operative and restorative techniques, and effectively separated dentistry from the wider category of surgery".[63][64]

A modern dentist's chair

A modern dentist's chair

After Fauchard, the study of dentistry rapidly expanded. Two important books, Natural History of Human Teeth (1771) and Practical Treatise on the Diseases of the Teeth (1778), were published by British surgeon John Hunter. In 1763, he entered into a period of collaboration with the London-based dentist James Spence. He began to theorise about the possibility of tooth transplants from one person to another. He realised that the chances of a successful tooth transplant (initially, at least) would be improved if the donor tooth was as fresh as possible and was matched for size with the recipient. These principles are still used in the transplantation of internal organs. Hunter conducted a series of pioneering operations, in which he attempted a tooth transplant. Although the donated teeth never properly bonded with the recipients' gums, one of Hunter's patients stated that he had three which lasted for six years, a remarkable achievement for the period.[65]

Major advances in science were made in the 19th century, and dentistry evolved from a trade to a profession. The profession came under government regulation by the end of the 19th century. In the UK, the Dentist Act was passed in 1878 and the British Dental Association formed in 1879. In the same year, Francis Brodie Imlach was the first ever dentist to be elected President of the Royal College of Surgeons (Edinburgh), raising dentistry onto a par with clinical surgery for the first time.[66]

Hazards in modern dentistry

[edit]

Main article: Occupational hazards in dentistry

Long term occupational noise exposure can contribute to permanent hearing loss, which is referred to as noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) and tinnitus. Noise exposure can cause excessive stimulation of the hearing mechanism, which damages the delicate structures of the inner ear.[67] NIHL can occur when an individual is exposed to sound levels above 90 dBA according to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Regulations state that the permissible noise exposure levels for individuals is 90 dBA.[68] For the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), exposure limits are set to 85 dBA. Exposures below 85 dBA are not considered to be hazardous. Time limits are placed on how long an individual can stay in an environment above 85 dBA before it causes hearing loss. OSHA places that limitation at 8 hours for 85 dBA. The exposure time becomes shorter as the dBA level increases.

Within the field of dentistry, a variety of cleaning tools are used including piezoelectric and sonic scalers, and ultrasonic scalers and cleaners.[69] While a majority of the tools do not exceed 75 dBA,[70] prolonged exposure over many years can lead to hearing loss or complaints of tinnitus.[71] Few dentists have reported using personal hearing protective devices,[72][73] which could offset any potential hearing loss or tinnitus.

Evidence-based dentistry

[edit]

Main article: Evidence-based dentistry

There is a movement in modern dentistry to place a greater emphasis on high-quality scientific evidence in decision-making. Evidence-based dentistry (EBD) uses current scientific evidence to guide decisions. It is an approach to oral health that requires the application and examination of relevant scientific data related to the patient's oral and medical health. Along with the dentist's professional skill and expertise, EBD allows dentists to stay up to date on the latest procedures and patients to receive improved treatment. A new paradigm for medical education designed to incorporate current research into education and practice was developed to help practitioners provide the best care for their patients.[74] It was first introduced by Gordon Guyatt and the Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group at McMaster University in Ontario, Canada in the 1990s. It is part of the larger movement toward evidence-based medicine and other evidence-based practices, especially since a major part of dentistry involves dealing with oral and systemic diseases. Other issues relevant to the dental field in terms of evidence-based research and evidence-based practice include population oral health, dental clinical practice, tooth morphology etc.

A dental chair at the University of Michigan School of Dentistry

A dental chair at the University of Michigan School of Dentistry

Ethical and medicolegal issues

[edit]

Dentistry is unique in that it requires dental students to have competence-based clinical skills that can only be acquired through supervised specialized laboratory training and direct patient care.[75] This necessitates the need for a scientific and professional basis of care with a foundation of extensive research-based education.[76] According to some experts, the accreditation of dental schools can enhance the quality and professionalism of dental education.[77][78]

See also

[edit]

Medicine portal

Medicine portal

- Dental aerosol

- Dental instrument

- Dental public health

- Domestic healthcare:

- Dentistry in ancient Rome

- Dentistry in Canada

- Dentistry in the Philippines

- Dentistry in Israel

- Dentistry in the United Kingdom

- Dentistry in the United States

- Eco-friendly dentistry

- Geriatric dentistry

- List of dental organizations

- Pediatric dentistry

- Sustainable dentistry

- Veterinary dentistry

Notes

[edit]

- ^ Whether Dentists are referred to as "Doctor" is subject to geographic variation. For example, they are called "Doctor" in the US. In the UK, dentists have traditionally been referred to as "Mister" as they identified themselves with barber surgeons more than physicians (as do surgeons in the UK, see Surgeon#Titles). However more UK dentists now refer to themselves as "Doctor", although this was considered to be potentially misleading by the British public in a single report (see Costley and Fawcett 2010).

- ^ The scope of oral and maxillofacial surgery is variable. In some countries, both a medical and dental degree is required for training, and the scope includes head and neck oncology and craniofacial deformity.

References

[edit]

- ^

Neil Costley; Jo Fawcett (November 2010). General Dental Council Patient and Public Attitudes to Standards for Dental Professionals, Ethical Guidance and Use of the Term Doctor (PDF) (Report). General Dental Council/George Street Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- ^ "Glossary of Dental Clinical and Administrative Terms". American Dental Association. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Stone age man used dentist drill". BBC News. 6 April 2006. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ Suddick, RP; Harris, NO (1990). "Historical perspectives of oral biology: a series". Critical Reviews in Oral Biology and Medicine. 1 (2): 135–51. doi:10.1177/10454411900010020301. PMID 2129621.

- ^ "When barbers were surgeons and surgeons were barbers". Radio National. 15 April 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ "dentistry". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ a b Gambhir RS (2015). "Primary care in dentistry – an untapped potential". Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care (Review). 4 (1): 13–18. doi:10.4103/2249-4863.152239. PMC 4366984. PMID 25810982.

- ^ "What is the burden of oral disease?". WHO. Archived from the original on 30 June 2004. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry | Dental CE Courses". aacd.com. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ a b c "Diagnosis of Celiac Disease". National Institute of Health (NIH). Archived from the original on 15 May 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

cite web: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ^ Dental Enamel Defects and Celiac Disease (PDF) (Report). National Institute of Health (NIH). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016.

- ^ Pastore L, Carroccio A, Compilato D, Panzarella V, Serpico R, Lo Muzio L (2008). "Oral manifestations of celiac disease". J Clin Gastroenterol (Review). 42 (3): 224–32. doi:10.1097/MCG.0b013e318074dd98. hdl:10447/1671. PMID 18223505. S2CID 205776755.

- ^ Estrella MR, Boynton JR (2010). "General dentistry's role in the care for children with special needs: a review". Gen Dent (Review). 58 (3): 222–29. PMID 20478802.

- ^ da Fonseca MA (2010). "Dental and oral care for chronically ill children and adolescents". Gen Dent (Review). 58 (3): 204–09, quiz 210–11. PMID 20478800.

- ^ Owen, Lorrie K., ed. (1999). Dictionary of Ohio Historic Places. Vol. 2. St. Clair Shores: Somerset. pp. 1217–1218.

- ^ Mary, Otto (2017). Teeth: the story of beauty, inequality, and the struggle for oral health in America. New York: The New Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-62097-144-4. OCLC 958458166.

- ^ "History". Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ^ Zadik Yehuda; Levin Liran (January 2008). "Clinical decision making in restorative dentistry, endodontics, and antibiotic prescription". J Dent Educ. 72 (1): 81–86. doi:10.1002/j.0022-0337.2008.72.1.tb04456.x. PMID 18172239.

- ^ Zadik Yehuda; Levin Liran (April 2006). "Decision making of Hebrew University and Tel Aviv University Dental Schools graduates in every day dentistry—is there a difference?". J Isr Dent Assoc. 23 (2): 19–23. PMID 16886872.

- ^ Zadik Yehuda; Levin Liran (April 2007). "Decision making of Israeli, East European, and South American dental school graduates in third molar surgery: is there a difference?". J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 65 (4): 658–62. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2006.09.002. PMID 17368360.

- ^ Gelbier, Stanley (1 October 2005). "Dentistry and the University of London". Medical History. 49 (4): 445–462. doi:10.1017/s0025727300009157. PMC 1251639. PMID 16562330.

- ^ a b Gelbier, S. (2005). "125 years of developments in dentistry, 1880–2005 Part 2: Law and the dental profession". British Dental Journal. 199 (7): 470–473. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.4812875. ISSN 1476-5373. PMID 16215593. The 1879 register is referred to as the "Dental Register".

- ^ a b "The story of dentistry: Dental History Timeline". British Dental Association. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ^ J Menzies Campbell (8 February 1955). "Banning Clerks, Colliers and other Charlatans". The Glasgow Herald. p. 3. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ "History of Dental Surgery in Edinburgh" (PDF). Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. Retrieved 11 December 2007.

- ^ "Dentistry (D.D.S. or D.M.D.)" (PDF). Purdue.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ "Canadian Dental Association". cda-adc.ca. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ "Anesthesiology recognized as a dental specialty". www.ada.org. Archived from the original on 21 September 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ "Sports dentistry". FDI World Dental Federation. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ "AVDC Home". Avdc.org. 29 November 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- ^ "EVDC web site". Evdc.info. Archived from the original on 5 September 2018. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- ^ Barras, Colin (29 February 2016). "How our ancestors drilled rotten teeth". BBC. Archived from the original on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- ^ "Oldest Dentistry Found in 14,000-Year-Old Tooth". Discovery Channel. 16 July 2015. Archived from the original on 18 July 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ "Analysis of Neanderthal teeth marks uncovers evidence of prehistoric dentistry". The University of Kansas. 28 June 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ Oxilia, Gregorio; Fiorillo, Flavia; Boschin, Francesco; Boaretto, Elisabetta; Apicella, Salvatore A.; Matteucci, Chiara; Panetta, Daniele; Pistocchi, Rossella; Guerrini, Franca; Margherita, Cristiana; Andretta, Massimo; Sorrentino, Rita; Boschian, Giovanni; Arrighi, Simona; Dori, Irene (2017). "The dawn of dentistry in the late upper Paleolithic: An early case of pathological intervention at Riparo Fredian". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 163 (3): 446–461. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23216. hdl:11585/600517. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 28345756.

- ^ Bernardini, Federico; Tuniz, Claudio; Coppa, Alfredo; Mancini, Lucia; Dreossi, Diego; Eichert, Diane; Turco, Gianluca; Biasotto, Matteo; Terrasi, Filippo; Cesare, Nicola De; Hua, Quan; Levchenko, Vladimir (19 September 2012). "Beeswax as Dental Filling on a Neolithic Human Tooth". PLOS ONE. 7 (9): e44904. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...744904B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044904. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3446997. PMID 23028670.

- ^ Coppa, A.; et al. (2006). "Early Neolithic tradition of dentistry". Nature. 440 (7085). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 755–756. doi:10.1038/440755a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 16598247.

- ^ "Dig uncovers ancient roots of dentistry". NBC News. 5 April 2006.

- ^ Bernardini, Federico; et al. (2012). "Beeswax as Dental Filling on a Neolithic Human Tooth". PLOS ONE. 7 (9): e44904. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...744904B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044904. PMC 3446997. PMID 23028670.

- ^ "700 years added to Malta's history". Times of Malta. 16 March 2018. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018.

- ^ "History of Dentistry: Ancient Origins". American Dental Association. Archived from the original on 5 July 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- ^ TOWNEND, B. R. (1944). "The Story of the Tooth-Worm". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 15 (1): 37–58. ISSN 0007-5140. JSTOR 44442797.

- ^ Suddick Richard P., Harris Norman O. (1990). "Historical Perspectives of Oral Biology: A Series" (PDF). Critical Reviews in Oral Biology and Medicine. 1 (2): 135–51. doi:10.1177/10454411900010020301. PMID 2129621. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 December 2007.

- ^ a b c Blomstedt, P. (2013). "Dental surgery in ancient Egypt". Journal of the History of Dentistry. 61 (3): 129–42. PMID 24665522.

- ^ "Ancient Egyptian Dentistry". University of Oklahoma. Archived from the original on 26 December 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ Wilwerding, Terry. "History of Dentistry 2001" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ^ "Medicine in Ancient Egypt 3". Arabworldbooks.com. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- ^ a b "History Of Dentistry". Complete Dental Guide. Archived from the original on 14 July 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ "History of Dentistry Research Page, Newsletter". Rcpsg.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ a b Donaldson, J. A. (1980). "The use of gold in dentistry" (PDF). Gold Bulletin. 13 (3): 117–124. doi:10.1007/BF03216551. PMID 11614516. S2CID 137571298.

- ^ Becker, Marshall J. (1999). Ancient "dental implants": a recently proposed example from France evaluated with other spurious examples (PDF). International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants 14.1.

- ^ Malik, Ursman. "History of Dentures from Beginning to Early 19th Century". Exhibits. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Renfrew, Colin; Bahn, Paul (2012). Archaeology: Theories, Methods, and Practice (6th ed.). Thames & Hudson. p. 449. ISBN 978-0-500-28976-1.

- ^ "Dental Treatment in the Ancient Times". Dentaltreatment.org.uk. Archived from the original on 1 December 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- ^ Bjørklund G (1989). "The history of dental amalgam (in Norwegian)". Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 109 (34–36): 3582–85. PMID 2694433.

- ^ Czarnetzki, A.; Ehrhardt S. (1990). "Re-dating the Chinese amalgam-filling of teeth in Europe". International Journal of Anthropology. 5 (4): 325–32.

- ^ Meri, Josef (2005). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia (Routledge Encyclopedias of the Middle Ages). Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-96690-0.

- ^ Friedman, Saul S. (2006). A history of the Middle East. Jefferson, N.C.: Mcfarland. p. 152. ISBN 0786451343.

- ^ Gregory Ribitzky. "Pelican". Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ^ Gregory Ribitzky. "Toothkey". Archived from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ^ Gregory Ribitzky. "Forceps". Archived from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ^ Royal Commission on the NHS Chapter 9. HMSO. July 1979. ISBN 978-0-10-176150-5. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ a b André Besombes; Phillipe de Gaillande (1993). Pierre Fauchard (1678–1761): The First Dental Surgeon, His Work, His Actuality. Pierre Fauchard Academy.

- ^ a b Bernhard Wolf Weinberger (1941). Pierre Fauchard, Surgeon-dentist: A Brief Account of the Beginning of Modern Dentistry, the First Dental Textbook, and Professional Life Two Hundred Years Ago. Pierre Fauchard Academy.

- ^ Moore, Wendy (30 September 2010). The Knife Man. Transworld. pp. 223–24. ISBN 978-1-4090-4462-8. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ^ Dingwall, Helen (April 2004). "A pioneering history: dentistry and the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh" (PDF). History of Dentistry Newsletter. No. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2013.

- ^ "Noise-Induced Hearing Loss". NIDCD. 18 August 2015.

- ^ "Occupational Safety and Health Standards | Occupational Safety and Health Administration". Osha.gov.

- ^ Stevens, M (1999). "Is someone listening to the din of occupational noise exposure in dentistry". RDH (19): 34–85.

- ^ Merrel, HB (1992). "Noise pollution and hearing loss in the dental office". Dental Assisting Journal. 61 (3): 6–9.

- ^ Wilson, J.D. (2002). "Effects of occupational ultrasonic noise exposure on hearing of dental hygienists: A pilot study". Journal of Dental Hygiene. 76 (4): 262–69. PMID 12592917.

- ^ Leggat, P.A. (2007). "Occupational Health Problems in Modern Dentistry: A Review" (PDF). Industrial Health. 45 (5): 611–21. doi:10.2486/indhealth.45.611. PMID 18057804. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 April 2019.

- ^ Leggat, P.A. (2001). "Occupational hygiene practices of dentists in southern Thailand". International Dental Journal. 51 (51): 11–6. doi:10.1002/j.1875-595x.2001.tb00811.x. PMID 11326443.

- ^ Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group (1992). "Evidence-based medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine". Journal of the American Medical Association. 268 (17): 2420–2425. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03490170092032. PMID 1404801.

- ^ "Union workers build high-tech dental simulation laboratory for SIU dental school". The Labor Tribune. 17 March 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ Slavkin, Harold C. (January 2012). "Evolution of the scientific basis for dentistry and its impact on dental education: past, present, and future". Journal of Dental Education. 76 (1): 28–35. doi:10.1002/j.0022-0337.2012.76.1.tb05231.x. ISSN 1930-7837. PMID 22262547.

- ^ Formicola, Allan J.; Bailit, Howard L.; Beazoglou, Tryfon J.; Tedesco, Lisa A. (February 2008). "The interrelationship of accreditation and dental education: history and current environment". Journal of Dental Education. 72 (2 Suppl): 53–60. doi:10.1002/j.0022-0337.2008.72.2_suppl.tb04480.x. ISSN 0022-0337. PMID 18250379.

- ^ Carrrassi, A. (2019). "The first 25 year [Internet] Ireland: ADEE (Association for Dental Education in Europe)". Association for Dental Education in Europe. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

External links

[edit]

Dentistry

| |

| Specialties |

- Endodontics

- Oral and maxillofacial pathology

- Oral and maxillofacial radiology

- Oral and maxillofacial surgery

- Orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics

- Pediatric dentistry

- Periodontics

- Prosthodontics

- Dental public health

- Cosmetic dentistry

- Dental implantology

- Geriatric dentistry

- Restorative dentistry

- Forensic odontology

- Dental traumatology

- Holistic dentistry

|

| Dental surgery |

- Dental extraction

- Tooth filling

- Root canal therapy

- Root end surgery

- Scaling and root planing

- Teeth cleaning

- Dental bonding

- Tooth polishing

- Tooth bleaching

- Socket preservation

- Dental implant

|

| Organisations |

- American Association of Orthodontists

- British Dental Association

- British Dental Health Foundation

- British Orthodontic Society

- Canadian Association of Orthodontists

- Dental Technologists Association

- General Dental Council

- Indian Dental Association

- National Health Service

|

| By country |

- Canada

- Philippines

- Israel

- United Kingdom

- United States

|

| See also |

- Index of oral health and dental articles

- Outline of dentistry and oral health

- Dental fear

- Dental instruments

- Dental material

- History of dental treatments

- Infant oral mutilation

- Mouth assessment

- Oral hygiene

|

Cleft lip and cleft palate

| |

| Related specialities |

- Advance practice nursing

- Audiology

- Dentistry

- Dietetics

- Genetics

- Oral and maxillofacial surgery

- Orthodontics

- Orthodontic technology

- Otolaryngology

- Pediatrics

- Pediatric dentistry

- Physician

- Plastic surgery

- Psychiatry

- Psychology

- Respiratory therapy

- Social work

- Speech and language therapy

|

| Related syndromes |

- Hearing loss with craniofacial syndromes

- Pierre Robin syndrome

- Popliteal pterygium syndrome

- Van der Woude syndrome

|

National and international

organisations |

- Cleft Lip and Palate Association

- Craniofacial Society of Great Britain and Ireland

- Interplast

- North Thames Regional Cleft Lip and Palate Service

- Operation Smile

- Overseas Plastic Surgery Appeal

- Shriners Hospitals for Children

- Smile Train

- Transforming Faces Worldwide

- Smile Angel Foundation (China)

|

Authority control databases  |

| National |

|

| Other |

- Historical Dictionary of Switzerland

- NARA

|